Leabhar-latha

-

Rory Green

“Micro-cyclic salt in the wind and the trees,

And the thick low mist oscillating in the breeze,

The sunset dips and the cumuli freeze,

And giant metal sentinels emerge from the sea”

Leabhar-latha is a sprawling emergence from my time in Cromarty. Inspired by historic texts, local people and the surrounding area, the project draws from folktales, locations, states of mind I experienced, and attempts to translate elements of my own concepts through ambient sound and electronic music. Taking its name from the Gaelic word for diary, or directly translated as “day-book” the name felt appropriate as the songs are often culminations of how I spent a specific day, or was inspired by a passage from a book, usually Hugh Miller’s Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland (1835). For those interested, the picture behind is of me taking a recording in Drooping Cave, on the shore of the South Sutor.

I’d like to take this opportunity to thank several people for contributing to the project in some way, the scope of which exceeded what I thought I could handle in a month, so huge thanks to…

Georgia, Gail, Susan, Helena, Rachel, Dave (Newman,) David (Alston,) Mary, Paul, Iona, and of course Rylan.

I’d also like to thank everyone else I met in Cromarty; those who Rylan and I shared dinners with, drank pints with, danced with, chatted to, and who shared their lives with us in any way. For fear of leaving anyone out I didn’t want to list you all here, but you know who you are. You all made it an experience I’ll cherish forever, and I hope to see you again very soon. Apologies also for feeble and inconsistent referencing.

Points of Interest

Overarching Composition Methods & Leabhar-latha Part I: Signals

The opening track Signals was initially a test drive for the overarching methodology. Using a poem that I’d written, (top of this article,) I began to test how I could draw from text to create music with modular synth (this is roughly the modular setup I had at the time https://www.modulargrid.net/e/racks/view/1566504). Aside from the identifiable tonality of the poem, (slightly ominous, although clearly an expression of my twinkly eyed wonder upon arrival in Cromarty,) there are already some sounds we can draw from; the sentinels (rigs,) emerging from the sea, the wind in the trees etc. Identifying sounds is obviously an easy first step in the sonification process, but what interested me more was the synesthetic crossover between sound and physiological texture. I was reading Nan Sheperd’s The Living Mountain (1977) at the time, and was particularly drawn to her fixation, (as outlined by Robert Macfarlane in the foreword of my copy,) with sensations of touch whilst exploring the world around her.

Sounds can communicate physiological phenomena; sounding dry, or wet, or soft, or sharp, or warm, or cold. Here we find the phenomenological point of interest I wanted to perforate all of my work at the residency. The sensations present in my poem include but are not limited to;

- Cyclic salt on the wind, dryness of the lips, coldness and motion

- Moisture in the mist contrasting the dryness, airborne condensation

- Cold sea water on the metal of the rigs, metallic, mechanistic entities contrasting an otherwise naturalistic landscape

- Vapour in clouds freezing, gaseous bodies becoming solid

These kinds of analyses helped inspire sound design within my modular synth. I feel quite strongly that the perceptions around materials which are synesthetically linked to specific sound categories are inherently informed by the actual sounds made by the materials themselves. For example, communicating the rusted metal of the rigs can be characterised by scraping, flaking, or metallic sounds, or resonant booms, as if made by interacting with the surface of the metal itself. This isn’t always true however, mixing lightly saturated (distorted) analog polyphonic synth chords and then filtering them is generally (in sound design circles,) accepted as sounding “warm,” but why is this? How can a sound be reminiscent of a temperature? Connotations of old recording gear overheating, or the crackle of a fireplace spring to mind, but these kinds of melancholic connotations are quite hard to pin down/define. Without wanting to overanalyse I just went with what my ears enjoyed. If a little whispering flicker sound felt reminiscent of dust on a tombstone, or if a synthy chord swell felt like how the wind behaves around MacFarquar’s Bed, then those noises would characterise the song.

I also wanted to punctuate as many of the works as possible with un-synced triggering, essentially having sounds jitter and dance around free of the overall grid-locked tempo of the song, (many songs are completely void of tempo.) This is clearly audible in Leabhar-Latha Part I. Sweeping noisey transients, which I think I intended to sound something like the sensation of pine needles in the wind or insects scuttling on the skin scamper throughout the tune. Off grid sound topographies seemed to me to communicate naturalistic phenomena much more effectively than gridlocked song structures.

Clarsach Grains & Generative Music

This song, (Rylan’s favourite from my work from the residency and possibly mine too,) contains only two sound sources. One is a small knocking sound from my modular that can be heard when the percussion comes in, but every other sound is drawn directly from a short recording of me messing around with the clarsach that lives in Ardyne House. All of the other drums, melodies, textures and atmospheres come from editing and processing that single piece of audio. One of the melodies which was created procedurally using generative granular synthesis, (basically a system whereby a portion of audio is held, and little snippets or “grains” are fired out at random,) is my favourite of any generative melody I’ve ever created.

Generative sound synthesis makes up a huge part of how I compose and is always exciting as you’re never sure exactly whats going to come out. I use generative techniques to try and create melodic structures and sound design that I wouldn’t usually think of. It basically means to designate some part of the writing/sound design process to algorithms that typically include chance and randomness. You can randomise anything; notes in a melody, parameters controlling sound shaping, timings of certain transients occurring and pretty much anything else you can think of. I’d refer anyone to Chapter 11 Generative Strategies in Curtis Road’s Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic (2015) to learn more about generative music. I find that generative systems help me breach my own imaginative boundaries, and have historically helped practitioners reach beyond their own creative limitations.

Rylan and the Wind

One day early on in the residency, I wasn’t sure if it was the wind I was hearing or someone singing. Of course it turned out to be Rylan, so I positioned a microphone in such a way that it captured predominantly the wind, with Rylan’s tones drifting very gently through. Sometimes Rylan had the foreground in the recording, sometimes the wind did, and there was some interesting interplay between the two. The attempt was to confuse the recording in the same way I had been confused, with Rylan’s voice and the sound of the wind grappling for the foreground in the perspective of the listener. This recording was then sampled into my modular synth and run through all manner of effects and modulation. I did the same again in my computer.

Resonators

Digital resonators were used extensively in both the modular synth and software applications across the project. They essentially allow you to digitally simulate and sculpt a virtual resonant corpus, such as the body of a drum or gong, or string of a violin, and many other noise making bodies. You can then “excite” this corpus, (such as “striking,” “bowing,” or “blowing” on the virtual corpus,) with signals generated within the resonator itself, or, crucially, external audio signals. Both corpus and exciter can be modulated endlessly, so the resonant body sounds like its shifting, from glass to metal to wood, from small and tinny to enormous and boomy, drum to string, cavern to branch.

I found that processing more traditionally “synthy” sounds with resonators made them sound a lot more “real,” and thus tied into folkloric/traditional themes a little better. Exciting the resonator sometimes sounded like animal calls, or tribal drums or distant flutes. I spent many hours getting lost in shifting resonators. Looking back, I feel incredibly lucky to have been given the opportunity to spend so long in aimless noisemaking.

Running a melodic exciter into a resonator is also interesting because you can harmonize the with resonator itself. You can send one melodic pattern into the resonator, and then have another melody control the pitch of the resonator, creating harmony. You can also do this with two resonators, one into the other. Imagine bowing the string of a violin with the string of a separate violin, but your playing harmonized melodies on both. Then imagine the violins are shifting from violins made of glass, to flutes made from stone, to drums made from plastic, and everything in between. Its pretty limitless and fun to explore. For more information on resonators and modal synthesis see the following articles:

https://www.music.mcgill.ca/~gary/307/week10/modal.html – (McGill University, 2004-2021)

https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~bilbao/booktop/node14.html - (Bilbao, 2006)

Thoughts on Being a Ghost

I have a bit of an overactive imagination, and traipsing through the streets, beaches, caves, woods or graveyards at night to get recordings often got me feeling a bit spooked. It eventually occurred to me how creepy a presence I must have appeared to anyone who saw me. Standing stock still at the harbour holding a microphone up to the wind at 3am, or playing back siren song from Drooping Cave at dusk, or any of the peculiar tones emanating from any writing sessions outside or in the crypt or the churches must have been strange for passers-by to notice. While this loosely informed my practice, I just included it as it seems funny considering anyone previously wondering whether or not they’d seen a green lady, could now be reading this thinking “oh that’s what that weirdo was doing…”

Morial’s Den

Morial’s Den was my favourite piece to produce. I wanted to draw from the Legend of Morial’s Den, (found in Scenes and Legends, it’s a good’n,) and also to visit the hollow where the legend takes place and produce the whole track there. Taking my OP-1 portable synthesizer (https://teenage.engineering/products/op-1) along the Bayview I turned left into the hollow and scrambled through bracken and hawthorn until the undergrowth opened out to where the stream rolled over exposed rocks. I sat there for a couple of hours writing and recording until the sun went down and stumbled back down to the road in the dark.

Footage:

https://www.instagram.com/p/CWibMVaKxr6/

Contextualising a piece with a folktale and then being able to visit the actual location of the story is really enthralling. It was one of my favourite days of the residency; huddled in the hollow in the gloom of sundown with the stream running by and considering how easy it would have once been to believe that one might come here and have “an interesting encounter with one of the unknown class of spectres” (Miller, 1835.)

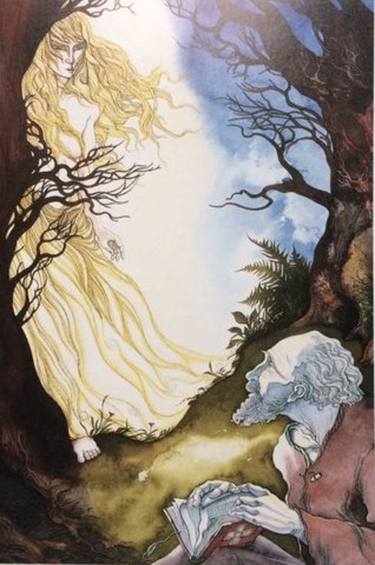

Morial’s Den - Christopher E. Fry

Murmur on the Shore

Murmur on the Shore intends to convey the physiological surroundings of Macfarquar’s Bed; a bay across the South Sutor from Cromarty. From the top of the Sutor you cross a few fields and break down into a sharp decline, down a path thick with gorse on either side.

To me, the whole place felt like it was breathing. The way the wind was channeled by the rock formations and the way the waves drifted up them made the whole place feel like a giant lung. I tried to capture this in the song, blissful tranquility and airy sound design, with lax downtempo percussion. This is one of the less explicit sound design examples. Synthesized sounds represent physical surfaces, (rocks, waves, sand, wind,) without imitating the sonic behaviour all that much. Melody and harmony convey the emotions I felt whilst wandering in the bed.

The East Church

Every sound in the tune was made by/recorded with the harmonium in the east church.

In the Wind’s Own Language

This track was a real mesh of different folkloric and physiological points of interest, all centered around the sea. The title comes from Scenes and Legends as Miller discusses how sailors would whistle to the wind to coax it into blowing. You can hear my pitch-shifted whistling throughout the tune, and the accelerating harp melody represents the wind picking up. Other superstitious sounds included are siren song, produced using vocal formant synthesis and then played back and recorded in Drooping cave, (pictured below,) as well as a knocking sound, that was said to be a premonition for someone drowning. Someone also told me a story about a ghost who was said to have walked on the seafloor in the bay, and also that Miller once used rocks to freedive down to imagine it, hence the feelings of descendance/submergence that arrive a little after two minutes in.

Live Set

This was my second time playing live modular to people, so I wanted to try my best to keep things simple where possible. Instead of structuring the set too tightly, I set up more of a jam system that I could improvise with, and just practiced on it until I knew it like the back of my hand. I wanted to ingest some of the aforementioned off-grid random sound triggering, and set up some parts of the patch where I could control the rate of certain noise transients from spaced out stabs all the way up to continous self oscillating textures. It was fun to ingest live texture control as well as programming in melodies and controlling tonal parameters, which is something I’ll incorporate into live sets in future.

The bottome line with the live set was to make it fun to play. I feel quite strongly that a room full of people watching someone struggle with a next of cables and get frustrated/panicked makes for an unenjoyable experience for everyone. I wanted to set up a system I could just noodle away on for 30 minutes.

References

Bilbao, S. (2006). Modal Synthesis. For Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics. Stanford University. [Website]. Available at: https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~bilbao/booktop/node14.html

McGill University (2004-2021) Modal Synthesis. [Web pages, various] (Updated 2021) Available at: https://www.music.mcgill.ca/~gary/307/week10/modal.html

Miller, H. (1835). Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland, or, The Traditional History of Cromarty. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black

Roads, C. (2015). Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic. New York: Oxford University Press

Sheperd, N. (1977). The Living Mountain. Edinburgh: Aberdeen University Press

Contents